The Challenge:

In 2015 I was asked to help with a root cause analysis to investigate the poor performance of some projects in an engineering consulting firm’s portfolio. This article uses “fake” numbers, but they are similar (in the aggregate) to some extracted from an actual accounting database. When I entered the discussion the cause was assumed to be percentage cost of sales. Digging into the data resulted in different conclusions (and remedies) and underscored why using the right metrics for project profitability is critical.

In 2015 I was asked to help with a root cause analysis to investigate the poor performance of some projects in an engineering consulting firm’s portfolio. This article uses “fake” numbers, but they are similar (in the aggregate) to some extracted from an actual accounting database. When I entered the discussion the cause was assumed to be percentage cost of sales. Digging into the data resulted in different conclusions (and remedies) and underscored why using the right metrics for project profitability is critical.

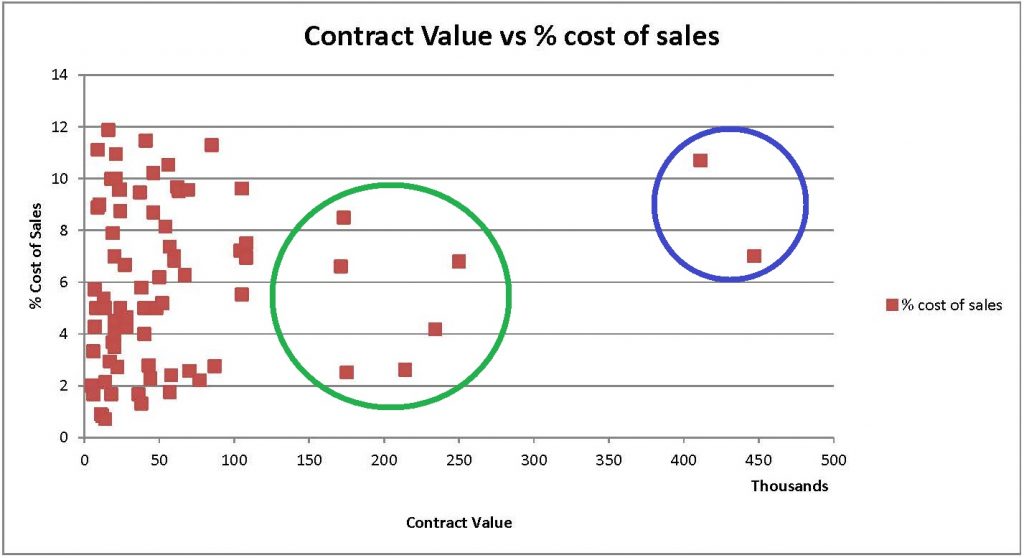

These projects had been flagged as having very high sales costs as a percentage of revenue. Since there is a minimum amount of work required to win any project (even if it’s nothing more than writing an email proposal) a commonly used practice is to look at the cost of sales (the effort required to win a contract) as a percentage of the value of the project. This metric is the percent cost of sales. While larger projects tend to require more effort (a bigger proposal) to win than smaller projects, in general larger projects have a smaller percent cost of sales, since a $12,000 proposal for a $400,000 project is much smaller (as a percentage) than a $200 proposal (an email) for a $5,000 project.

There was a “healthy debate” in the boardroom when I arrived, and one group was suggesting that the company avoid these large expensive projects and focus exclusively on smaller projects (which had been the core business of the company for much of the last decade). Another group was pushing back, pointing out that while the larger projects were not as profitable, their size and length made it possible to hire additional staff and ramp up the size of the company. After some discussion we all sat down and the team presented the following graph, showing the size of the project compared with the cost of sales, very similar to the one below.

There were a number of mid-sized projects that looked quite attractive (green circle) but more than half of the small projects for the year had a lower cost of sales than either of the two large projects. Perhaps more striking is that many companies will simply not bid on projects where the expected cost of preparing a proposal is more than 5% of the contract value, and roughly half of the projects were more than the 5% maximum cost of sales that *should* have been applied. Something was clearly odd, and the cost of sales seemed to be out of control! Given that most companies of this type tend to have a 10% (or less) profit margin that would suggest that one of the two large projects was actually costing the company money, and the second wouldn’t be adding much to the bottom line.

Down the Rabbit Hole

Asking how the company was doing in terms of overall finances provided an interesting answer – the previous year had been one of their highest revenue years, and that it had been slightly more profitable than an average year – almost 18% profit before taxes. While the team was good, I didn’t think that they were more than twice as good as the average company in their industry – which they would have to be if they were making profits at that level after incurring massive sales costs!

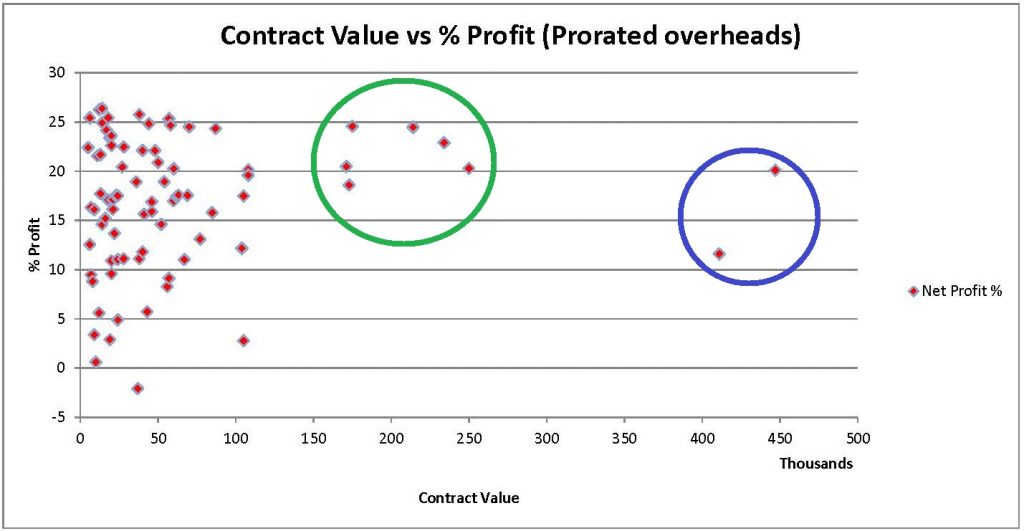

To see if we could get a better handle on what was actually happening, I asked if we could get a graph showing project size against profitability, as a percentage of contract size. Crunching the data in this way, suddenly the “high cost” projects (in blue) started looking much more attractive: the reason that cost of sales is an important metric is because if it “costs” too much to get a sale then your overall business is unprofitable. These numbers suggested that the large projects were carrying their own weight. But this plot looked a little too pretty – at least some projects should be expected to lose money, and according to this data, only one project was unprofitable in the last year!

Looking into the cluster of mid-sized projects (In the green circle around $150-$250k) there was general agreement that these were not “outliers”, but projects that had resulted from the natural progression of some medium-sized ($25-$50k) projects. Proposal costs were invariably low, and effectiveness was very high, since the project teams already knew what needed to be done and were already familiar with the projects (and the clients). If there was only one kind of project to do, these would be the projects – but there was no way of knowing which medium opportunities would lead to this kind of follow-on work.

At this point one of the people involved in the less profitable of the large projects asked how profitability was calculated – he knew that the proposal costs for his project had been moderate (considerably less than the cost of sales percentage had indicated) and the project metrics were comparable (although larger in scale) to some of the extremely profitable mid-sized projects. After some discussion, it was discovered that the accounting system did not track “overheads” (like invoicing) to a specific project, but instead applied them pro-rated to the projects based on contract value – assuming that a $400k project would require 100x the administrative overhead of a $4k project.

So after this discussion, we have a question as to where the “unprofitable” projects are, and exactly what costs should be applied to each project.

A Reality Check

Because of the way that overheads were calculated, there was no way to determine what the historic overhead costs were, but it was clear that the large projects were carrying a disproportionate share of the overhead burden. Instead of spending several months (and increasing the overhead burden) collecting this information, a rough breakdown of costs was determined based on the typical length of projects and their accounting complexity. Regardless of the size of the project, a certain amount of time was needed by the accounting team to set up a project, create appropriate project codes and close the project. The other major factor was monthly billing, with large projects taking up to 2x the amount of time to issue invoices every month as the smaller projects, and their typical duration was 5-9 months, while a small project was often created and closed in a single month. reallocating provided a very different graph, which had many of the “large project” proponents feeling vindicated, and the “small project” group scratching their heads.

Notice that we now have a “tail” of low value projects that are unprofitable, and the large projects are almost as profitable as the mid-value projects that were acknowledged as the best projects that the company could pursue.

All Projects Are Not Created Equal

At this point we had a reversal of what we thought we were looking at: the larger projects were uniformly profitable (although those mid-sized projects were awesome) and we had a mix of projects that were profitable, and those that were extremely unprofitable. So what was the difference between them?

By looking at the specific projects associated with each data point, it is possible to look into what they were. Small projects can become unprofitable if there is any scope or schedule risk associated with them. On a small project (less than $5k) with expected profit margins in the 10% range almost any overrun will put them in the red – a $3,000 project is typically completed in under a week, so a 1/2 day overage is going to happen before many folks do their timesheet and realize that their budget is blown! On the other side of the coin, profitable small projects are often projects with a defined scope and a work product that is well refined: two classic examples are small change orders (which are treated as separate “projects”) and “projects” that are really best thought of as part of a portfolio, such as GIS mapping, desktop analysis or environmental site assessments. Companies may deliberately have these cluster in the “unprofitable” zone to be used as loss leaders to get further work. Environmental Site Assessments are often done at a loss by companies that use site remediation as their main revenue source.

Looking into the specifics identified a couple of the projects in the “tail” as being projects that had a very high proposal cost, which then set up very inexpensive project wins for larger follow-on projects. There was also a cluster of projects in the $10-$25k range which averaged about 15% profitability associated with an Environmental Site Asessment (ESA) business unit – which was very well characterized and extremely cost competitive.

What Does This Mean For You?

One of the general trends that is being applied across many consulting firms is a minimum contract size threshold. While this article uses synthetic data it was configured so that it would reflect the trends we see with actual accounting data. The typical lower threshold for smaller consulting firms is generally in the $10-$15k range, and some firms have trouble with anything under $25k being profitable. This threshold gets murkier if you can’t pull costs of sales and project-specific overhead costs out of your accounting systems.

As we saw earlier, if you track overhead as a “bucket” that gets pro-rated back to projects the picture *looks* better – often to the point that you will go “it looks like there might be a problem with little projects, but we don’t really need to take corrective action…” As soon as you are tracking actual costs against the projects that incurred them (even if you have to fudge the numbers and set a minimum cutoff) the smaller projects lose some of their “subsidy” from the larger projects and become more marginal.

Since the immediate thing that most folks concentrate on is “how do I optimize the projects that are unprofitable” is almost invariably “it depends”. If you have a lot of projects that are very similar then handling them as a portfolio generally works – overheads are consolidated, execution on all of the “sub-projects” can be optimized, and these often become very profitable (and incidentally start to look like $60K+ projects)

The usual cause for unprofitable small projects is that they aren’t similar, and it takes a chunk of admin overhead for ALL projects, big or small (usually on the order of $1,000-$5,000 regardless of the size of the project) to enter the project in your internal systems, do the monthly accounting etc. a lot of that “tail” is usually hidden because folks don’t track overhead by project, but just pro-rate the overhead based on a percentage of invoicing – so that $200k project absorbs more of the “overhead” budget than the $10k project.

Instead of trying to “fix” issues with these small projects, choosing to not do projects below a certain threshold improves profitability: net profit for this sample portfolio is 12.8% on $4.785M, but if you simply choose not to do any projects under $15k this improves to 13.3% on $4.165M. This is obviously fallacious, since you still need to pay rent and the salaries of all of your staff, but dropping those less profitable projects and replacing them with projects similar to the rest of your projects will have the same effect on your (percent) profitability. Of course if you don’t have enough work, then you probably won’t choose to be this draconian, but the effort chasing those small projects (in this example 20% of projects were under $15k) could be spent in chasing large projects. Alternately aggregating the projects into portfolios (as discussed earlier) would also improve their profitability, and improve both the top and bottom lines.

Another thing to be aware of before you decide that the only thing you should chase is large projects – larger projects take more time (and thus resources) to win, and generally spend more time in the “sales funnel”`before you can start working on them. This means that there is a longer delay between investing the money to win them and being able to see the results, and if you don’t win these it will have a significant effect on your bottom line.

So What Happened?

Before issuing decrees like “We aren’t doing any project under $15k!” it is important to recognize that many “big” projects (often with tiny proposal costs associated) are often landed as a result of doing strategic small projects, or small projects which grow into big projects.

The recommendation provided to handle these competing demands (while following the PM Mantra “no surprises”) was a new policy flagging projects under a set threshold (in this case $15k) as “no bid” projects. To pursue a strategic proposal required a gatekeeper (A VP in this case, although this could be a business unit lead in a larger company) needs to provide approval. This approval process doesn’t need to be anything complex: an email stating why this project should be pursued, followed by an email response to approve the project is usually enough, but you want something that you can save with the initiation documentation to understand why this project was pursued. At the end of the year when reviewing these (unprofitable) projects, the cost can be lumped where it belongs – as a cost of business development.

To assist in tracking what is going on with these strategic projects you need a way to flag the connection between “loss leader” small projects and their larger follow-on projects. This will let you associate the total proposal costs with the aggregate project value so you can track the information needed to steer your company’s profitability.

Scott Martin

Photo Credit Benjamin Child – https://unsplash.com/@bchild311